Counter-Punching on the Mudzi

D Company, 1RAR, on Operation Mardon, 1 November 1976

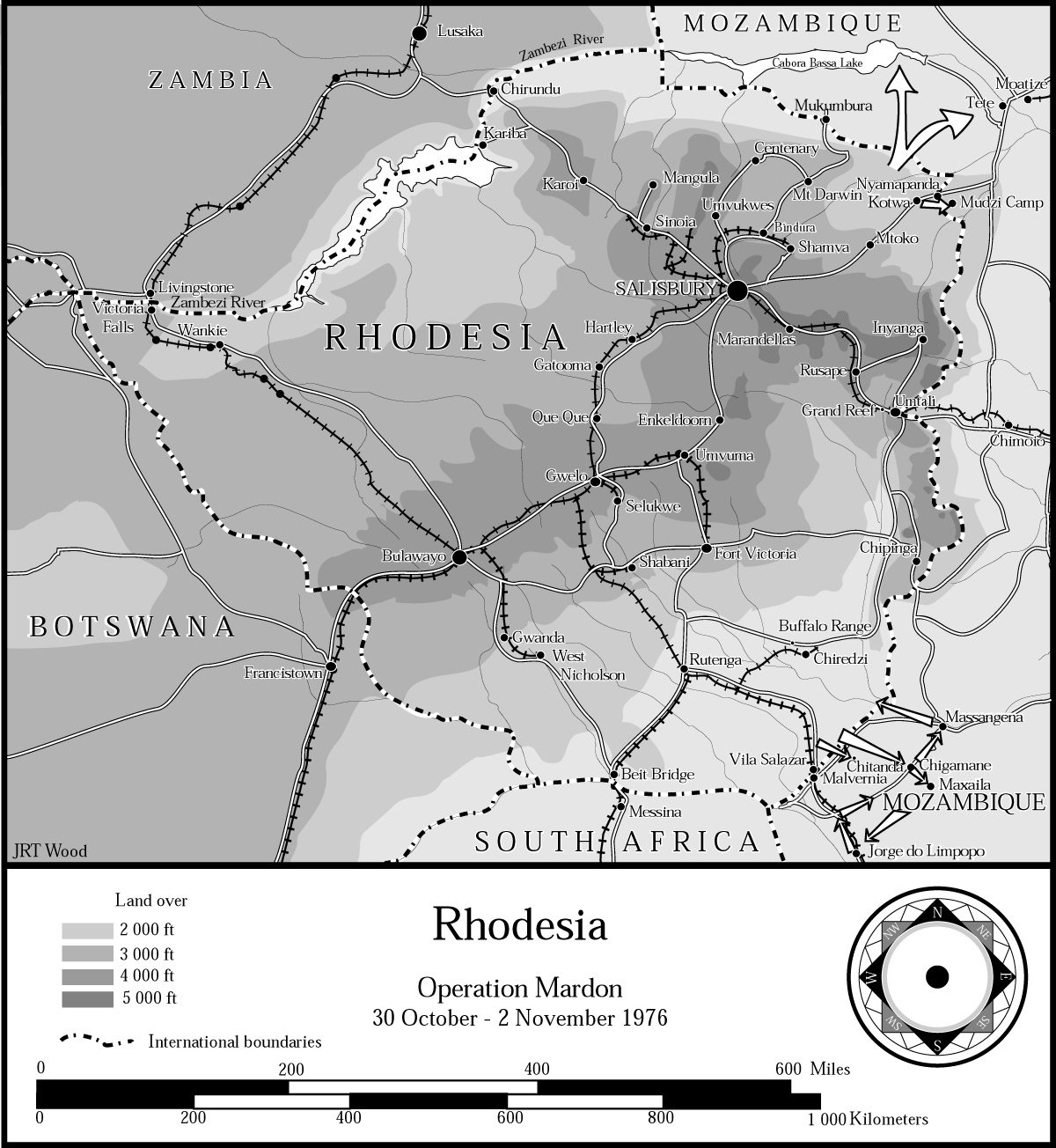

Firstly The Daily Telegraph of London, on 28 October 1976, and then the Observer of 31 October reported the infiltration that month of hundreds of African nationalist fighters into Rhodesia from Mozambique. They were reinforcing the armed cadres of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) - the military wing of Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) - who had been waging guerrilla warfare in the eastern half of Rhodesia with varying intensity since late 1972. The British pressmen claimed that there were 2 000 insurgents operating inside Rhodesia by the end of October, and that another 8 000 were poised to enter from Mozambique. These claims were largely true and incidents, including attacks on vital railway lines and trains, had doubled in October. The Rhodesian security forces counter-punched with a series of intensive operations within the country. October 1976 saw the heaviest fighting of the war: 26 Rhodesian servicemen, 144 insurgents, and 84 civilians caught in between, died in the action.

This guerrilla influx coincided not just with the start of the rainy season and the rapid spring growth of vegetation to cover ZANLA's operations. Adhering to the dictum of Mao Tse Tung that 'You cannot win at the conference table what you have not won on the battlefield', ZANLA was attempting to strengthen Robert Mugabe's hand at the Rhodesian settlement conference which opened on 28 October in Geneva, Switzerland. The conference (destined to be abortive) was the consequence of events around 23 September 1976. On that day in Pretoria, South Africa, Henry Kissinger, then the US Secretary of State, combined with B.J. Vorster, the South African Prime Minister, to confront Ian Smith. Although Smith had defied the world since declaring Rhodesia unilaterally independent in 1965, Kissinger succeeded in convincing him that he now faced overwhelming odds, that he had no alternative but to commit Rhodesia to the implementation of universal suffrage within two years if there were to be any prospect of ending Rhodesia's international estrangement and the crippling consequences thereof. The result was a settlement conference with delegates from all parties, including Mugabe's ZANU and the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) of his insurgent rival, the veteran African nationalist, Joshua Nkomo.

To weaken Mugabe before and during the Geneva Conference, the Rhodesian security forces redoubled their counter-insurgency effort within Rhodesia and launched Operation Mardon against the ZANLA build-up of forces in Mozambique. D-Day was 31 October and the operation was to be over by 2 November. Mardon comprised simultaneous strikes into Mozambique against ZANLA camps, the destruction of the logistical support, and the mining of supply and infiltration routes. The attacks were to be across the north-eastern and south-eastern borders by regular units of the Rhodesian Army, supported by the Rhodesian Air Force.

There had been similar operations across the south-eastern border with Mozambique in mid-1976 and in August, the Selous Scouts had launched a major vehicle-borne attack eastwards against the main ZANLA base at Nyadzonya, some 50 kilometres into Mozambique. They had killed more than a thousand insurgents.

The purpose of Mardon was not just to blunt the ZANLA offensive. It was also to persuade ZANLA to cease infiltrating across the flat terrain of the border areas in the north-east and south-east in favour of coming in directly from the east. There they had to move through mountainous country which favoured both their easy detection and the use of vertical envelopment by the helicopter-borne infantry of Fire Force. Fire Force exploited the agility of the helicopter in quickly surrounding infiltrators and eliminating them.

The Special Air Service (SAS), the Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI), the Grey's Scouts (horse-mounted infantry) and detachments from the Corps of Engineers were detailed by Mardon's planners to attack targets to the north-east in the Tete Province of Mozambique. A Selous Scouts' column of armed vehicles was to attack to the south-east, down the line of rail in Gaza Province, seeking targets as far as Mapai, 100 kilometres away. Simultaneously, the white officers and African soldiers of A Company, the Second Battalion, the Rhodesian African Rifles (2RAR), commanded by Major André Dennison, would walk across the south-eastern border to attack Chitanda Camp on the Chefu River, also in Gaza.

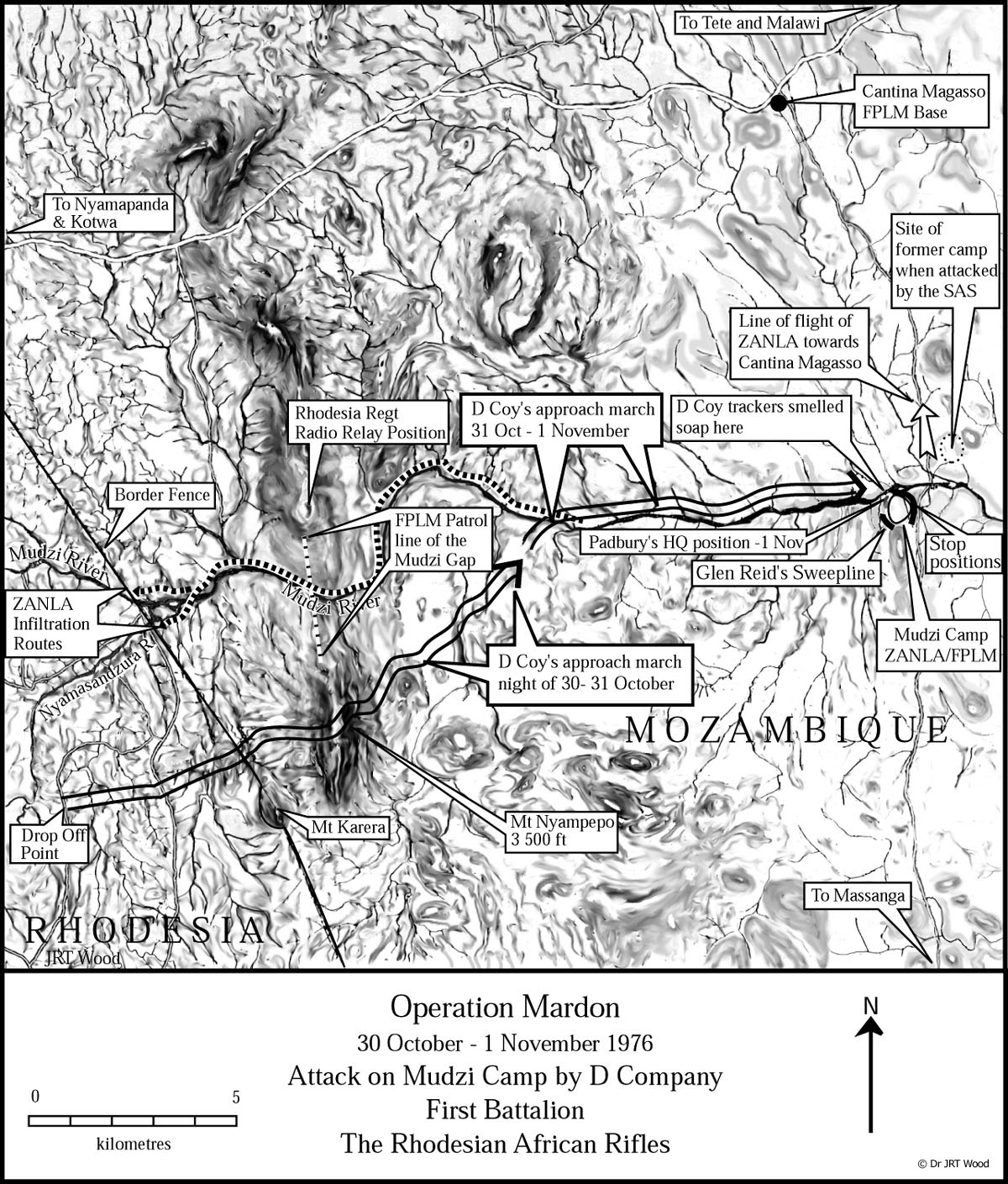

The planning got under way in mid-October and the Selous Scouts reconnaissance teams were deployed into Mozambique on 18 October. The Two Brigade Intelligence Officer, Lieutenant Bob Warren-Codrington of the SAS, however, wanted a wider effort and pressed the Operations Co-ordinating Committee (OCC) for an additional attack in the north-east on ZANLA's Mudzi Camp some 15 kilometres into Mozambique (south-east of the border village of Nyamapanda and eight kilometres south of the main road to Malawi through Mozambique).

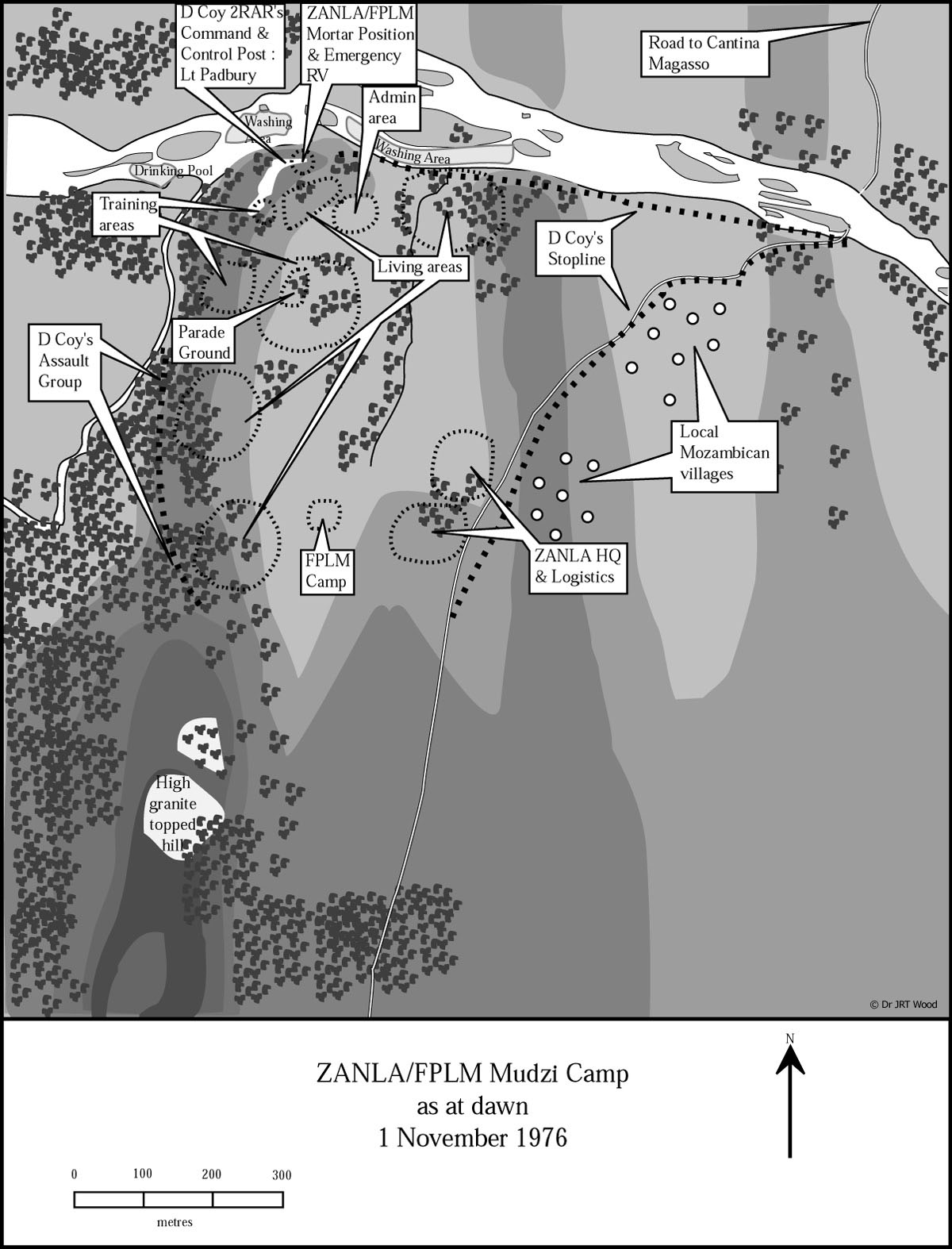

Although there was some training at it, Mudzi Camp served as the main transit base for ZANLA infiltration into the Rhodesian Mudzi and Inyanga North Tribal Trust Lands which flanked the Mozambican border south of Nyamapanda. The camp had a permanent complement of Mozambican Army (FPLM) and Tanzanian troops to provide protection and logistical support. In addition, there was some civilian labourers, maintaining the camp. The OCC relented 48 hours before D-Day, and D Company, the First Battalion, Rhodesian African Rifles (1RAR), commanded by Major Graham Noble, was given the target.

D Company, 1RAR, was one of the more experienced companies of the battalion which was then deployed in the north-east under command of the Joint Operations Centre (JOC) at the airfield at Mtoko (now Mutoko - 100 kilometres north-east of Salisbury - now Harare). In reality, however, although its African troops were battle-hardened professionals, D Company had just received an intake of new young white platoon commanders - including Second Lieutenants Alistair Hope and Tony Clarke. In addition, it had a freshly joined Second in Command, Captain Glen Reid, late of the US Special Forces, who had already proved to be the most determined of soldiers. To strengthen the command team therefore with someone who knew both the troops and the ground, JOC Mtoko decided to bring in a former D Company platoon commander of long-standing, Lieutenant David Padbury, who was currently the Battalion Intelligence Officer.

Then on a helicopter tour of the various infantry companies deployed by JOC Mtoko, Padbury was ordered back to the headquarters to be told on arrival that he was to command the assault group - a strengthened platoon, some 40 men strong. He, and his batman, Private John Selete, had grown used to the comparatively easy life of a staff officer and his servant. So to get their bodies and minds in order, in the hours before departure, Padbury took Selete on a quick run in full kit around Mtoko airfield to shake off the cobwebs.

Reinforced with trackers and mortar crews from Support Company, 1RAR, Graham Noble and D Company were given 24 hours in which to prepare. They were briefed at JOC Mtoko on Friday, 29 October, by Warren-Codrington who was assisted by Captain Ken Johnson, second in command of the Joint Services Photographic Interpretation Service (JSPIS). The briefing was based on a reconnaissance report from the Selous Scouts and 'B2' radio intercept information. Warren-Codrington explained that, after an earlier SAS attack, Mudzi Camp had been moved from the northern to the southern bank of the Mudzi where the track from Massanga (directly south on the Ruyena River) crossed a drift in the river. Bordered by the river in the north, the camp now lay in a basin between two parallel northward running ridges, stemming from a large high granite-domed hill to the south. The latest air photographs showed the target covered by dense cloud (masking some nasty surprises for D Company), so older photographs had to be used for the planning. Although the Scouts' report said that the camp held a few dozen ZANLA, it was seen as a worthwhile target as part of the overall harassment of ZANLA.

As serious resistance was not anticipated, and because all available aircraft of the small Rhodesian Air Force were assigned to cover the operations of the SAS, RLI and Selous Scouts elsewhere in Mozambique, air support was denied to D Company. A single Alouette III helicopter 'G-Car' was put on stand-by at Mtoko for casualty evacuation only. In any case, until 1977, the Rhodesian government was loathe to bomb targets in newly-independent Mozambique for fear of international repercussions.

By Selous Scout calculations, D Company would reach Mudzi Camp in the early hours of Sunday, 31 October, ready to launch a dawn attack in co-ordination with the rest of Mardon's operations. To get there, the heavily-laden troops faced a night march of 20-21 kilometres over mountainous terrain and through the thick bush of the broken country along the southern bank of the Mudzi River. The load per man was in fact more than normal, as extra 7.62mm MAG machine-guns had been issued to increase the potency of the force. This meant that the men would be festooned with extra MAG ammunition belts. An MAG gunner could expect his gun and ammunition to weigh 26.45 kg (56 lbs). He would also be laden with his fighting kit, his food and water. With the Mudzi River mostly dry at that time of year, after the six-month winter drought, and the weather hot, water was an important ingredient for success. In addition, the four Support Company 81mm (short-barrelled) mortars had to be carried. Each mortar broke down into three-man loads (the base plate, the barrel, and the bipod and sight, weighing together 37.85 kgs or 83.45 lbs). To have sufficient mortar ammunition for the attack, the 40 men of Padbury's assault group would be carrying one or two 4.45 kg mortar bombs plus their personal weapons, ammunition, rations and water.

After the briefing, David Padbury took care to study the air photos further with the help of Captain Johnson. As events turned out, it was fortuitous that he did this.

On Saturday, 30 October, its hasty preparations complete, D Company drove on the main road to its forward assembly point at Kotwa, close to Nyamapanda. At Kotwa, the troops fed, refreshed themselves and refuelled the vehicles for the final leg of the journey eastwards to the drop off point across the dirt roads through the bush of the Mudzi Tribal Trust Land. This point was some four kilometres from the Mozambican border just south of the junction of the Nyamasandzura and Mudzi Rivers (flowing out of Rhodesia from the west).

The battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Shute, arrived at Kotwa to wish D Company 'God-speed' and to set up the tactical headquarters (TAC HQ) there from which to control the operation. At the moment that the troops climbed aboard their vehicles to depart, Major Noble threw the operation into confusion by suddenly falling sick and announcing to Shute that he was too ill to go any further. Command therefore devolved in a hasty hand-over onto his second in command, Captain Glen Reid.

Having to compensate for the loss of Noble but with no time to lose, if D Company were to reach its start point on time, Reid and Padbury were forced to do a great deal of re-organising aboard the vehicles en route. Reid decided that, because Padbury knew the terrain and the conditions better than he did, Padbury should take over Noble's task of guiding D Company to the target. Thereafter, Reid proposed to control the battle while, as planned, Padbury led the assault. Padbury spent the time as the trucks drove eastwards studying the maps further, planning the coming night march.

The drop-off point was reached on time just after last light. The troops debussed, formed up and marched off, led by Padbury and the trackers, on the four kilometre initial leg across broken country to the border fence. Then, once in Mozambique, to avoid the FPLM patrol line guarding the ZANLA infiltration route into Rhodesia along the Mudzi River, Padbury faced D Company's burdened troops with a difficult and exhausting climb of a thousand feet in the dark, up and over the thickly bushed steep ridge of the peak of Nyampepo Mountain (3 100 feet above sea-level). The exhaustion and difficulty of the slippery climb was sufficient for the assault group troops to start deliberately to discard the heavy mortar bombs. As the 81mm mortars were their only support weapons and because every bomb might be needed, a halt was called and the troops were spoken to severely. In addition, a rear party was detailed to ensure that no bombs or kit were discarded or lost deliberately. It was also impressed upon the troops that they were heading for a large camp where they would be outnumbered. No further losses were incurred on the march.

It took until after midnight to get D Company over Nyampepo and by then one of the casualties was Padbury himself, who slipped and hurt his back and hip in a fall of some metres down the mountain. Thereafter, the densely bushed difficult ground prevented D Company from making up time. Accordingly Reid and Padbury contacted Shute at TAC HQ Kotwa via the radio relay position, manned by the Rhodesia Regiment, on Nyampepo's twin peak (the two mountains are divided by the Mudzi River). They advised him that they had a problem of time and distance. They were some 6 000 metres short of the target and, with daylight not far off, they did not have time for a close-in reconnaissance which was essential because of the vagueness of the information on the camp, its whereabouts and its strengths. To preserve the element of surprise, they suggested that they spend the day where they were and renew their approach march at dusk for an attack at dawn the next day, 1 November. The TAC HQ concurred promptly, and D Company based up in the uninhabited thick bush of the hilly country south of the Mudzi River.

During a reconnaissance for water, a D Company patrol encountered and captured a Mozambican hunter and his dog near the Mudzi. Considering himself fortunate not to have been killed on the spot, he volunteered much useful information on the area and about the camp. He confirmed D Company's suspicion that the more open country on northern bank of the Mudzi was easier to travel along in contrast to the Selous Scouts' recommended heavily-bushed and broken southern route. Indeed he said that there were several good paths running to the east which allowed for rapid movement. These paths were not controlled by anyone and were used frequently not only by the local inhabitants but also by ZANLA cadres moving to and from Rhodesia. He also told his interrogators that the camp was large and that many people passed through it. It would be found, he said, on the southern bank. He was unsure on the size of its current population but said that there was much activity at it. As if in confirmation, D Company then heard shots fired from the direction of the camp and assumed that rifle training was taking place. The prisoner was detained for the day and then left that night tied to a tree beside one the paths and told to hold his tongue. He assured his captors that he considered himself very lucky indeed to be spared.

At last light D Company emerged from its hide to begin its night approach march to the camp. The first objective was to cross the wide dry sandy bed of the Mudzi with the minimum of delay, but the troops had to fill their water bottles from the pools which were scattered down its length - all that remained after the long dry season. The eastward paths, mentioned by their captive, were found easily and proved to be as good as he claimed. Progress was therefore rapid with the trackers well in advance, stopping the column frequently to allow them quick reconnaissance ahead to ensure that no sudden encounter with ZANLA or Mozambican FPLM in transit would give the game away. The good progress being made raised the morale of the troops after the difficulties of the previous night. They began to concentrate on the imminent attack.

After three hours of marching, at around 2100 hours, a halt was called close to the bank of the river because Padbury and his trackers could smell soap on the rocks and from the water of a long stagnant pool. The strength of smell indicated that a large number of people bathed there.

As the camp was obviously close by, it was decided to do a recce of the southern bank. Captain Reid delegated the task to David Padbury and Alistair Hope. They crossed the river, and climbed the steep rocky hill immediately above the precipitous southern bank. Climbing the rocks was so difficult that, close to the summit, to keep noise to a minimum, Padbury decided to go on alone, leaving his rifle and kit with Hope and keeping only his webbing, radio and pistol.

At the top, Padbury could discern in the dark a camp much larger than he had anticipated, stretching below him to the south and south-east. It was clear from the fires and other signs that there were not a few dozen ZANLA inhabitants as the Selous Scouts had reported but somewhere in the region of a thousand. The exact figure for the camp's population was never fully established but the conservative estimate was 800, made up of trained personnel waiting to infiltrate Rhodesia, recruits under training, recruits in transit from Rhodesia to Tete, some Rhodesian and local Mozambican civilians and the Mozambican FPLM and Tanzanian protection troops.

Padbury ascertained that the high ground on which he stood provided the ideal position for a command post. Searching around he also found a track that led down the boulder-strewn hill to the river behind him. Then he heard movement close to him on the hill and quietly retreated to Hope. They returned down the hill to the waiting D Company and reported to Captain Reid.

It was decided to march D Company up the feature because it was an ideal briefing point. The men moved silently and quickly up the track and at the summit the group commanders were given their final orders with the camp clearly discernible in the darkness below. As this was done, it was realised that, being in a basin between the east and west ridges emanating from the high granite hill to the south, the camp was a perfect bombing target. Accordingly, a long signal was sent to TAC HQ for an airstrike to initiate the attack. Reid and Padbury were seeking a bombing run by Canberras using the locally-invented and manufactured Mark Two Alpha bomb. This football-sized bomb was round and, by virtue of having hard rubber balls between its inner and outer casing and a three-way contact fuse, was designed to bounce two metres off the ground before exploding. The Canberra bomb-bays had been modified to take hoppers which dispensed the bombs in batches of a hundred at a time. The total bomb load was 300 bombs which enabled a single aircraft to cut a swathe of devastation 100 metres wide and 1 000 metres long. Without an airstrike, Reid argued, the attack would be less successful because the camp was larger than realised and D Company had insufficient men to contain the inhabitants. The initial assault by 40 men supported by four 81mm mortars would not achieve what a bombing run would. While they waited for a reply, Reid and Padbury planned stop positions along the bank of the Mudzi River on the northern edge of the camp to the Massanga Road, then down it, south to the high granite topped hill. It was immediately clear that, with only 100 D Company men, in 10-man stop-groups, to cover more than a kilometre and a half, ZANLA would not be trapped.

Padbury radioed the message twice but the TAC HQ was adamant that the aircraft were needed elsewhere. Replying the second time, the TAC HQ indicated, however, that although there would be no initial airstrike, the 1RAR Fire Force would be positioned at Kotwa to be available if needed during the action to bring out any casualties. This was a vital concession as it turned out. The Fire Force comprised a command gunship Alouette III helicopter or 'K-Car' (armed with a 20mm automatic cannon), three Alouette troop carriers or 'G-Cars' (armed with twin Browning Mk2 .303 machine-guns), and, as top cover, a Lynx (the Rhodesian name for a Reims-Cessna FTB 337G, 'push/pull' twin-engined light aircraft, armed with twin Browning .303 machine-guns, light rockets and bombs including napalm).

Appreciating that the stiffness from Padbury's back and hip injuries would hamper him in leading the assault group, Reid decided to take that task himself and ordered Padbury to act as co-ordinator. Padbury was to establish his command and control position among the boulders on the front, eastern face of the ridge where they stood to give him an unimpeded view of the battle.

The stop groups then departed for their positions along the Mudzi River and the east flank of the camp. Glen Reid took Alistair Hope, the assault group and the mortar crews back down to the Mudzi and a few metres westwards to the mouth of a dry tributary which flowed from the south behind Padbury's western ridge. This tributary was to be used as the Forming Up Point (FUP) by the assault group before they climbed the western ridge to use it as the start-line for the sweep forward and down into the camp under the mortar barrage. The western ridge dominating the camp was designated the Ground of Tactical Importance (GTI) because, whichever side held it, would control events.

During the departure of the troops, an MAG gunner and his number two became detached from their group in the darkness while still on the hill. They fell back to Padbury's position, reinforcing his small headquarters group which comprised himself, his radio operator, his batman and his MAG gunner and number two. The addition of another MAG and a rifleman was to prove crucial as what David Padbury could not know was that his end of the ridge was designated by ZANLA as their ‘crash RV’ (the emergency rendezvous). When dislodged by Reid's sweep line, the ZANLA fighters would run to regroup around his ridge which also had the ZANLA mortar position. (Later, when the battle was over and the clearing of the ridge began, mortars and RPG7 rockets were found, establishing this.)

It took time to march the troops around the large camp. One stop group blundered into a sleeping area near the Mudzi River and was challenged by sentries. The stop commander, Sergeant Saul, however, had been used previously by Padbury in the pseudo-terrorist role in intelligence gathering and had the presence of mind and the experience of ad libbing to answer in Shona that he was a ZANLA cadre bringing in recruits from Rhodesia, that he was tired and did not want to be ordered about. His reply was accepted and he was told to move on and find a place to sleep until morning when they would allocate him an area of the camp and debrief him. Sergeant Saul told David Padbury later that he had nearly burst out laughing as he moved off.

In the pre-dawn light of Monday, 1 November, the camp, as seen from Padbury's command post, seemed even larger and more formidable. The sounds of the insurgents awakening, moving about and then being drilled and trained drifted up. Training was taking place below his command post and Padbury could see a parade ground, just south of him, and living areas which had not appeared on the air photos. His stop groups were in place covering what ground they could but the attack was being delayed by the difficulty that the assault troops and the mortar crews were having in getting into position through the entangled vegetation of the steep re-entrant. Worse still the GTI, the western ridge running south in front of Glen Reid, appeared to be occupied. By now all the camp was coming alive. Movement was intensifying as the light strengthened and the assault group faced the problem of a fight upwards in full daylight before it could get to its intended start line and attack down the east face of the ridge into the camp.

With the brightening of the day, there was a sudden increase in the tempo of events. Over the radio, Platoon Warrant Officer Barnard, a stop group commander, urgently informed Padbury that a 40-strong group was moving towards his position. Could he open fire? Padbury reluctantly replied: 'Negative' because Glen Reid was still not nearly ready.

Almost immediately, movement in the trees below him drew Padbury's attention. A six-man clearance patrol was climbing up towards his position, and he identified them as Tanzanians by their uniforms. Contacting Reid, Padbury warned that, as contact between his men and the Tanzanians was imminent, the shooting was going to start before either the assault group or the mortars had reached the start line.

Tucked in behind boulders below the summit of the ridge, Padbury and his six men waited for the Tanzanians to walk into them. There was, Padbury recalls, an awful silence as if everyone, everything, man and nature, was waiting in great anticipation for something to happen.

Then it did. The six Tanzanians walked into the D Company command position and were shot at. Four of them fell where they were. The other two ran off, needlessly shouting the alert. Firing erupted all over the camp. The stop groups were in action immediately against the clearance patrol and other groups. Still moving, the mortar crews began their barrage while leap-frogging each other until they found a secure position from which to dominate the battle. Their fire was nonetheless remarkably effective. The hills echoed to the drumming barking fusillades of machine-guns, assault rifles and to the explosions of mortars, grenades, rockets. Every weapon to hand on both sides was fired. To the radio relay station on its mountain some 12 kilometres westwards it sounded like a major battle of the Second World War. Such was the intensity of the firefight that its sounds reached the forward airfield at Kotwa, 27 kilometres away, where the Fire Force waited.

Much of the fire from the camp was directed increasingly at Padbury's position, shattering the trees around him, sending a rain of broken branches down on him. As the exchange of fire intensified, Padbury and his men became aware of a determined effort to overrun them. Padbury's two MAG gunners probed the rocks below them with hammering bursts while the riflemen sought targets. The well-trained gunners did not flinch despite the heavy fire they drew. The MAG gunner and his number two closer to Padbury displayed cool team-work as they systematically covered the ground in front of them. When an RPG7 rocket burst above them, the gunner turned his head, shook it, and went back to firing. All seven RAR men fought a desperate battle for survival. Still the determination of the ZANLA assault did not wane.

Padbury's problem was deepened by the delayed arrival of the assault group. With the enemy alerted ahead of them, the group came under heavy fire as they reached the summit of the ridge. The fire slowed them down and they were in danger of losing momentum. It was only Captain Reid's good leadership and cool decision-making that kept the assault line moving forward over the ridge and into the camp.

As no help was yet forthcoming, Padbury was facing a desperate situation. In danger of being overrun, he took the decision to call down mortar fire onto his own position. The mortars responded quickly, providing a creeping barrage which Padbury directed towards himself. The bursting bombs had the desired effect. His attackers began to falter and, at that moment, at last, the assault line broke through into the main part of the camp, scattering the greater part of the insurgent force. Confronted by the determined RAR, ZANLA's nerve began to fail and the tide of battle turned in the attackers' favour. In their flight, many insurgents ran into the stop groups with Sergeant Saul's in particular reaping a grim harvest of dead.

At this stage, an RAR soldier was burnt by the blow-back of a phosphorous grenade he had thrown. Although the man was not seriously hurt, Captain Reid called for a casevac to get Fire Force in on the act. The Fire Force at Kotwa was scrambled, flying off without its troops but with Major Noble in command in the K-Car. It was quickly on the scene, its four helicopters orbiting the battlefield putting down supporting machine-gun and cannon fire, and providing Reid and Padbury with aerial observation. Driven back, the rump of the ZANLA resistance coalesced in groups but their bursts of rifle-fire enabled Padbury from his vantage point to pinpoint their position for the aircraft.

Padbury called the K-Car over to assess what remained of the threat to him. Locating a number of insurgents lurking in the rocks just beneath them, the K-Car ordered Padbury and his men to take cover and dealt with his attackers with lethal short bursts of 20mm cannon-shells. Nonetheless, as the K-Car flew over Padbury on its final pass before returning to Rhodesia to refuel, an insurgent fired an RPG7 rocket at it which burst underneath it, shaking it. The aircraft regained its even keel and led the Fire Force home.

An incoming Lynx replaced the helicopters, providing continued observation, acting as a radio relay to JOC Mtoko and ready to put down fire if needed. The assault was over and the troops were by now engaged in the slow work of clearing the camp, making a capture and destroying a large number of huts, bashas and equipment. Care had to be taken as a favourite ZANLA trick was to ambush clearing patrols among huts. Firing at the orbiting Lynx was heard to the south of the camp where some of the ZANLA had re-grouped but the bulk had fled northwards along the road towards Cantina Magasso, a small settlement on the main road, where they knew that the FPLM would protect them.

As calm returned to the command post and its seven men relaxed after their ordeal, David Padbury, directing the troops clearing below, was startled by a familiar voice interrupting him and intoning 'Your tea, Ishe.' A hand offered him a steaming mug. Padbury’s standing orders for his batman included that he expected to be served tea at dawn every day whatever the circumstances. So, unnoticed by his commander, in the anxious moments before the attack, the batman had busied himself behind his boulder with his butane-gas cooker, the kidney-shaped mug, the teabag and the milk. Throughout the attack, under heavy fire, John Selete had kept an eye on the mug of water slowly coming to the boil, all the while repulsing ZANLA with his FN rifle and reloading the empty metal link belts being spat out by the two MAGs flanking him. The action ceased when the tea was made and his officer was ready to drink it! Timed to perfection!

Before much progress had been made in clearing, the TAC HQ ordered Reid to regroup because radio intercepts were indicating that a large FPLM force was being deployed to trap D Company before it could escape back to Rhodesia. It had been intended that D Company would walk out but now it would have to be airlifted. As only two helicopters (capable of carrying four or five men at a pinch) were available at that time, it was clear that there was a lengthy process ahead. Nevertheless, this news was greeted with great relief by the troops. It had been a difficult approach march, a hard battle, and the prospect of a long exhausting climb over the mountains and the possibility of a fighting withdrawal had been daunting.

Regrouping took place on the northern bank of the Mudzi River, below Padbury's position, away from the potential residual dangers of the half-cleared camp. His position now became the observation point and the GTI for the defence of the area while the airlift took place. With morale high among the African soldiers, regrouping proceeded smoothly. A landing zone (LZ) was cleared in the dense bush and was secured by a defensive screen. Within an hour, at midday, the withdrawal began with the aircraft ferrying men to a secured position back in Rhodesia behind Mount Nyampepo 15 kilometres away. There the RAR had protection troops, a medic, food and water to greet the incoming weary men. To complicate the difficulties of taking out eight men at a time, the two helicopters were ordered to bring back as many ZANLA bodies and as much equipment as possible. This was for identification and to provide proof and evidence that an armed camp, not a refugee camp, had been attacked. The purpose was to neutralise the expected counter-propaganda from Mozambique and the rest of the world. The bodies had to be hauled out of the camp to the LZ across the dry river before being flown out, lengthening the laborious withdrawal. Most bodies were left where they fell and an accurate count was not undertaken because the clearing had not been completed. It was believed that more than 30 had died.

As the afternoon wore on, anxiety mounted as the radio intercepts uncovered an intensifying FPLM reaction. The FPLM were determined to trap the RAR in Mozambique, deploying troops and anti-aircraft guns along the border road. The helicopters, however, were never in much danger because the radio intercepts told where the guns were and thus the aircraft were able to fly well clear of them. If the FPLM attempt to box the RAR in came to nought, it did add to the sense of urgency to complete the withdrawal.

By late afternoon the airlift was finally over. Fifteen bodies, a large amount of equipment plus the 140 troops and their mortars had been flown out. In addition, a young three-year old African male child was brought out after being found by the troops near his dead parents who had been part of the camp staff. The RAR officers were moved by the compassion, emotion and concern shown by their tough African soldiers to this little casualty of war. The child was adopted by the regiment and brought up by a family at the barracks.

In the aftermath, D Company was debriefed and the troops were dispersed back to their internal operational areas. The attack by D Company on Mudzi Camp had achieved the highest kill rate on Operation Mardon and, without suffering any serious casualties, had struck a heavy blow to ZANLA morale. It was a testimony to the hardiness and effectiveness of the RAR soldiers - who spent most of their time on their two feet deep in the bush, carrying everything they needed on their backs, in the true role of the infantry soldier.

Elsewhere on Operation Mardon on the previous day, 31 October, the SAS and RLI had attacked the first targets in the Tete Province, on foot supported by mortars brought in on horseback by the Grey's Scouts after the engineers had breached the border minefields. After the initial attacks, 83 vehicles carried the troops in attacks on camps at Nura, Chicoa, Chicombizi and Gentu. Arms caches were unearthed and a tractor seized. Small numbers of ZANLA were killed for the loss of an RLI soldier, Trooper Graham Fanner, and an SAS operator, Trooper Ed Lotringer. A Grey Scout lost a leg in a detonation of a landmine which had been washed down a water course from the border minefield. As ZANLA fled towards the major town of Tete, the Rhodesians decided to pull back, having accomplished their aim.

In the south-east, in Gaza, targets were attacked by the Selous Scouts at Chigamane, Maxaila, Massangena and Jorge do Limpopo, where two troop-trains were destroyed along with the water reservoir and the switching points. Vehicles were ambushed. Among the captured was a FPLM paymaster with his escudos. The booty included a bus and quantities of arms and ammunition (all of which were put to good use on later raids). The blocking of the railway meant that ZANLA infiltrators had to walk the last 90 kilometres to the Rhodesian border before infiltrating.

The RAR's other attack was not as successful as that on the Mudzi. Unexpectedly thick bush, not betrayed by the small scale of the air photo, had hampered Major Dennison and his reinforced A Company, 2RAR (reinforced by elements of C Company and four 81mm mortars from Support Company) in their attack on Chitanga base just across the south-eastern border on the Chefu River. The flat country and the dense vegetation hampered his four 81mm mortar crews in their task of flushing out the camp towards stop groups which also had difficulty in deploying. Inaccurate fire from the mortars wounded two RAR soldiers, Corporal Kafakunesu and Private Tamudini of the assault line. Lieutenant Graham Schrag distinguished himself in a river bed, killing two insurgents. He was awarded the Bronze Cross of Rhodesia. The total kill was six as most of the ZANLA and FPLM were able to get away. In any case, the camp was almost empty as previously a group of 90 ZANLA, fleeing south-east from a contact in the Matibi 2 Tribal Trust Land, across the border in Rhodesia, had moved deeper into Mozambique 36 hours before. Dennison recovered documents, some ammunition and a few weapons. A ZANLA-laid landmine had the last word, exploding under one of A Company's vehicles on the road home to their base camp at Nyala Siding. Nine RAR soldiers were injured, six of them seriously.

With the last of the troops to leave Mozambique by 2 November being the Selous Scout column of vehicles after its round trip of 400 kilometres, the OCC's spokesman, Assistant Police Commissioner, Mike Edden, briefed the press. He justified Mardon by accusing ZANU of 'threatening . . . war while they're supposed to be talking peace'. He claimed that the raids had set back by two months ZANLA's plans for a major offensive by 1 700 men. Edden said that major military operations had taken place in the Tete Province of Mozambique and that the action in Gaza had been in retaliation for an earlier firing on the Rhodesian south-eastern border town of Vila Salazar. He did not give any casualty figures but said that no Mozambican soldiers or civilians had been killed. He added that the raid was meant to show 'that we are not weakening our military position.'

D Company had scored the highest kill of the operation but harassment, not killing, had been the overall aim of Operation Mardon. The results of all the attacks were impressive. Masses of captured documents yielded intelligence. Some 50 tonnes of war materials were destroyed and eight tonnes recovered to Rhodesia, including 150 British-made anti-tank landmines. The show of force, the attacks in depth with columns driving hundreds of kilometres, were intended to have a psychological effect, making ZANLA feel vulnerable in what hitherto had been safe havens. In addition, the destruction of railways, trains and the mining of roads hampered ZANLA's ability to deploy easily to the border. Above all, Mardon won the military initiative back into Rhodesian hands, at least for the moment, demonstrating that the security forces were far from being defeated, that they were not as weak as might have appeared by Smith's political surrender to Kissinger in September. The news of the successes raised Rhodesian morale while increasing the sense of vulnerability of the newly independent state of Mozambique.

The Mozambican response was a brief rocket attack on the eastern border city of Umtali but it caused no serious damage. The Mozambicans also used exaggeration for effect, to secure aid and sympathy from the outside world. They talked of Rhodesian tanks, aircraft and heavy artillery killing over 600 refugees.

The Rhodesians did not relax the pressure, however, and within days of Operation Mardon, the SAS and the RLI attacked the ZANLA base at Mavae in the Tete Province, killing 31.

When the Geneva conference, incompetently handled by its British chairman, Ivor (later Lord) Richard, came to its inevitable stalemate, Rhodesian morale rose further. The imminence of rule by Mugabe and his rival, Joshua Nkomo, seemed to fade and the threat of their armed followers seemed to diminish. In the three months of the Geneva Conference, 2 000 insurgents infiltrated Rhodesia but 321 were killed - an unprecedented number which contrasted with the 304 killed for the whole of 1975. Other options seemed possible.

Reference in bibliographies as "Counter-Punching on the Mudzi: D Company, 1RAR, on Operation Mardon, 1 November 1976", Dr J.R.T. Wood, www.jrtwood.com/article/counter-punching-on-the-mudzi, 1998"